As a political conservative, I am frequently branded as a racist. Nothing could be further

from the truth. I care deeply about Civil Rights and race relations.

My Dad, Dr. O. Norman Shands, was a minister in Atlanta, GA from 1953 – 1963. He

had exhibited a passion for Civil Rights from his time as a Chaplain in the Navy near the

end of World War II. In Atlanta, he served with Martin Luther King, Sr. on a standing

committee on relations between white and black Baptist ministers in the city. He had a

deep friendship with Dr. Benjamin Mayes, at the time the President of Morehouse

College, and, later the first African-American Superintendent of the Atlanta Board of

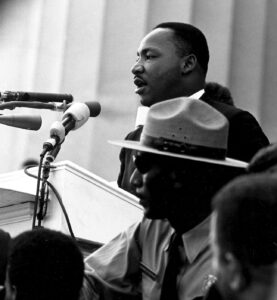

Education. Dr. Mayes was also a Baptist minister. Dad knew Dr. Martin Luther King,

Jr., and served on many symposiums with him. Dr. King, Jr. moved to Atlanta from

Montgomery, AL in December 1959. We moved away from Atlanta in July of 1963;

therefore, Dad’s relationship with Dr. King, Jr. did not have as much time to develop as

his relationship with Dr. Mayes and Dr. King, Sr.

Dr. King, Jr. was much more than a national figure to me, growing up in Atlanta from the

age of four to fourteen. He was known to me as an acquaintance of Dad’s and a topic

of many conversations at the dinner table. Dad made sure to convey to me that all

people are created in the image of God.

Atlanta was the first Southern city of any size in which the white, Protestant ministers

took a public stance in support of the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme

Court decision. Eighty ministers signed a manifesto, known as the 1957 Atlanta

Ministers Manifesto. It was published on the front page of the Sunday Atlanta Journal-

Constitution on November 3, 1957.

One of the signers of the Manifesto was a young Methodist minister, Dr. L. Bevel Jones

III. In his book, One Step Beyond Caution: Reflections on Life and Faith, ( ©Looking

Glass Books, 2001) Dr. Jones III aptly described the reaction many ministers received.

“I received a number of cold stares that morning as the congregation gathered. The

general public reacted more aggressively. My phone rang often in subsequent days,

and I received letters so hot I needed asbestos files. A few of them reflected adversely

on my ancestry.”

The reaction at Dad’s church, West End BAs a political conservative, I am frequently branded as a racist. Nothing could be further from the truth. I care deeply about Civil Rights and race relations.

My Dad, Dr. O. Norman Shands, was a minister in Atlanta, GA from 1953 – 1963. He

had exhibited a passion for Civil Rights from his time as a Chaplain in the Navy near the

end of World War II. In Atlanta, he served with Martin Luthe King, Sr. on a standing

committee on relations between white and black Baptist ministers in the city. He had a

deep friendship with Dr. Benjamin Mayes, at the time the President of Morehouse

College, and, later the first African-American Superintendent of the Atlanta Board of

Education. Dr. Mayes was also a Baptist minister. Dad knew Dr. Martin Luther King,

Jr., and served on many symposiums with him. Dr. King, Jr. moved to Atlanta from

Montgomery, AL in December 1959. We moved away from Atlanta in July of 1963;

therefore, Dad’s relationship with Dr. King, Jr. did not have as much time to develop as

his relationship with Dr. Mayes and Dr. King, Sr.

Dr. King, Jr. was much more than a national figure to me, growing up in Atlanta from the

age of four to fourteen. He was known to me as an acquaintance of Dad’s and a topic

of many conversations at the dinner table. Dad made sure to convey to me that all

people are created in the image of God.

Atlanta was the first Southern city of any size in which the white, Protestant ministers

took a public stance in support of the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme

Court decision. Eighty ministers signed a manifesto, known as the 1957 Atlanta

Ministers Manifesto. It was published on the front page of the Sunday Atlanta Journal-

Constitution on November 3, 1957.

One of the signers of the Manifesto was a young Methodist minister, Dr. L. Bevel Jones

III. In his book, One Step Beyond Caution: Reflections on Life and Faith, ( © Looking

Glass Books, 2001) Dr. Jones III aptly described the reaction many ministers received.

“I received a number of cold stares that morning as the congregation gathered. The

general public reacted more aggressively. My phone rang often in subsequent days,

and I received letters so hot I needed asbestos files. A few of them reflected adversely

on my ancestry.”

The reaction at Dad’s church, West End Baptist, was a little more moderate. Dad had

taken a very public stance of his own almost exactly one year prior at the annual

Georgia Baptist Convention. It also made front page news in the Atlanta Constitution,

accompanied by Dad’s picture addressing the convention. The reactions of our church

were quite negative, very nearly resulting in the termination of Dad’s pastorate.

I wrote a book about Dad’s activities in Atlanta, and in 2006 I published it. I won’t

belabor it here, but the title is In My Father’s House: Lessons Learned in the Home of a

Civil Rights Pioneer. I believe that his actions lit a match that resulted in the Manifesto.

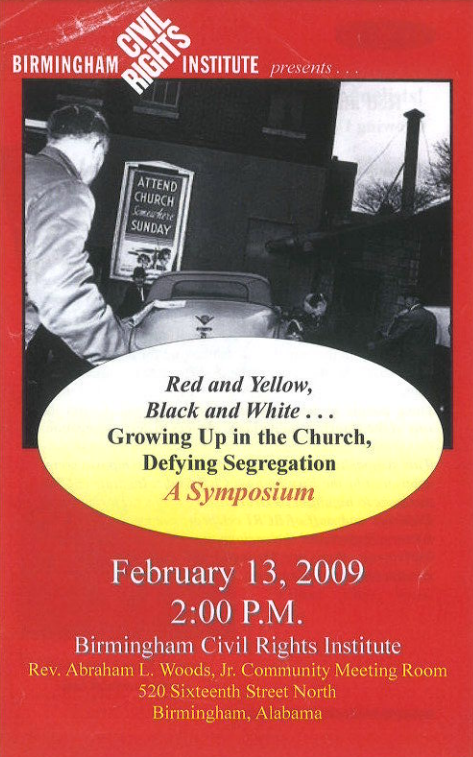

As a result of writing the book, I received several speaking opportunities. I cherish

having been invited to participate in a symposium at the Birmingham Civil Rights

Institute on February 13, 2009. The title of the symposium was “Red and Yellow, Black

and White . . . Growing up in the Church, Defying Segregation”. The other participants

were Dr. LeeAnn Reynolds, Ms. Deborah Smith, and Rev. Lamar Weaver. I will never

forget that Ms. Smith said that she had been very hateful towards whites as a child and

young adult, but the prayers of her pastor, which resulted in her joining in praying,

changed her heart. I firmly believe hatred is a matter of the heart, and the solution in

Jesus Christ.

If you have not been to the Institute, I certainly recommend that you make time to do so.

It is an experience that left me in awe. It sits across the street from the Sixth Street

Baptist Church, the site of a 1963 bombing that took the lives of four young black girls. In

another direction, it sits across from Kelly Ingram Park where, also in 1963, the

Birmingham police attacked civil rights demonstrators. The exhibit at the Institute

contains the bus that was burned in Anniston, AL in 1961 as the Freedom Riders

reached Anniston.

If you would like more information on the BCRI, please visit its website: bcri.org.